Archaeologists have excavated a trove of Stone Age human skeletons and artifacts on the shores of an ancient lake in the Sahara. The seven nearby sites include an extensive cemetery and represent one of the largest and best preserved concentrations of ancient skeletons and artifacts ever found in the region, researchers say. Harpoons, fishhooks, pottery, jewelry, stone tools, and other artifacts pepper the ancient lakeside settlement. The objects were left by early communities that once thrived on the former lake's abundant fish and shellfish.

"They were living on a diet rich in catfish, mollusks, and shells," said Paul Sereno, a University of Chicago paleontologist and National Geographic Society Explorer-in-Residence. "It was a place you could walk out the door of your hut amid the sand dunes and perhaps see hippos, elephants, giraffes, and crocodiles," he added. Sereno led a team of dinosaur fossil hunters that first discovered the archaeological site in 2000. The paleontologist returned to the site this September with an expedition co-led by Italian archaeologist Elena Garcea. The researchers found shells scattered on the dry lakebed and thousands of fossilized vertebrae from catfish that likely grew six feet (two meters) in length.

The remains "indicate that here were perennial waters in the area, and that certainly must have been one of the reasons so many people were attracted to it," said Garcea, speaking by telephone from her office at Cassino University in Italy. "I think that the area was a paradise on Earth for the people who were living there," she added. But just who were those people? Garcea says there is no single answer.

"This site doesn't represent a single period but a long period of time," she said. The team's radiometric analysis is not yet complete. But based on artifacts at the site, Garcea made a preliminary estimate that the area was occupied "between 10,000 and 5,000 or 4,000 years ago." The site may not have been continuously occupied. But it was likely inhabited for much of that time, which was a crucial one in early human history. During the New Stone Age, humans moved from hunter/gatherer societies to become early agrarians who domesticated plants and animals.

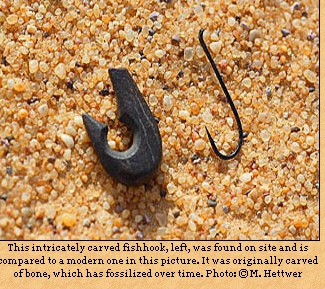

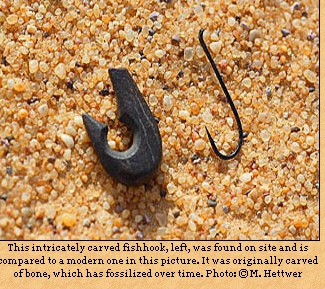

The region has long been arid. But it was a wetter, greener place at the end of the last Ice Age some 12,000 years ago. Early hunter/gatherer peoples, such as the Kiffian, apparently lived on the natural bounty provided by the ancient lake. Their remains still lie there, found in older archaeological layers and surrounded by harpoons, fishhooks, other tools, and remains of their catch. Tools such as large pottery and heavy grinding stones suggest that Kiffian peoples may have occupied the ancient lakeside area at least semi-permanently, Garcea says.

Scientists know that by about 6,300 years ago the Sahara's first pastoral people, the Tenereans, began tending herds of newly domesticated cattle. And while the expedition team found remains of domestic cows and asses, researchers are uncertain whether Tenerean peoples occupied the particular dig site.

The team says the site's human remains were most striking. Members found hundreds of skeletons in the site's large cemetery, some still adorned with ancient jewelry. The researchers found tools, such as precision stone blades, bone hooks, pottery stamps, and other artifacts, in graves and other site locations. Some artifacts suggest travel and perhaps even distant trade. Stone tools made of pale green volcanic rock could have their source some 50 miles (80 kilometers) distant in the Air Mountains, an area rich with period rock art.

The ancient lakeside settlements had long escaped discovery in the remote, sweltering, windy, area of Niger's Ténéré Desert. But during a hunt for dinosaur fossils in the area in 2000, expedition photographer Mike Hettwer discovered something quite unexpected. "'There are whole human skeletons just over there,' [Hettwer] said, pointing to a low ridge," Sereno wrote in a 2000 online dispatch from the field.

"Our jaws dropped as we tiptoed among skeletons that were buried thousands of years ago. Around the neck of one, we found a series of beads—the outline of a necklace!"

In 2003 Sereno returned to map the site and stopped counting at 173 skeletons, which easily made it the largest New Stone Age cemetery ever found in the Sahara. "We saw jewelry on the surface, tools everywhere, the remains of hundreds of people," Sereno recalled. "I knew that I had to help an archaeological team get a footing out there."

Sereno has accomplished that goal. But archaeologists are not the only ones who have visited the historic site. Niger is a poor nation, and the temptation to profit from its rich cultural history has proven too great for some. "We followed some 4x4 tracks that our guides said were definitely not made by tourists but by vendors going out there for stolen artifacts," Sereno said. "A photographer with our team estimates that he photographed as many as 3,000 artifacts in one day, found in shops of communities near the site."

The team employed secrecy to cover their tracks and protect the site from future plunderers. Sereno is also launching a major effort to achieve official protection for the site. "Part of our work in Niger has been … ultimately to save [these discoveries] for everybody," he said. Yet the unique site faces an even more daunting threat from Mother Nature. "The wind is destroying these sites very quickly," Garcea, the Italian archaeologist, said. "I saw pictures that [Sereno] took in 2003, and you can really see the deflation."

"Some skeletons that were covered are now exposed to the surface and the hyper-arid desert conditions. In two or three years I'm sure I won't be able to see some of the things that we can study now," she added. The team hopes to return next fall, when conditions should allow future exploration. "We can't wait too long," Garcea said, "because the wind is out there 365 days a year." Field updates from the expedition, including the most recent research, are available at Project Exploration ( www.projectexploration.org/niger2005/).